LLVM

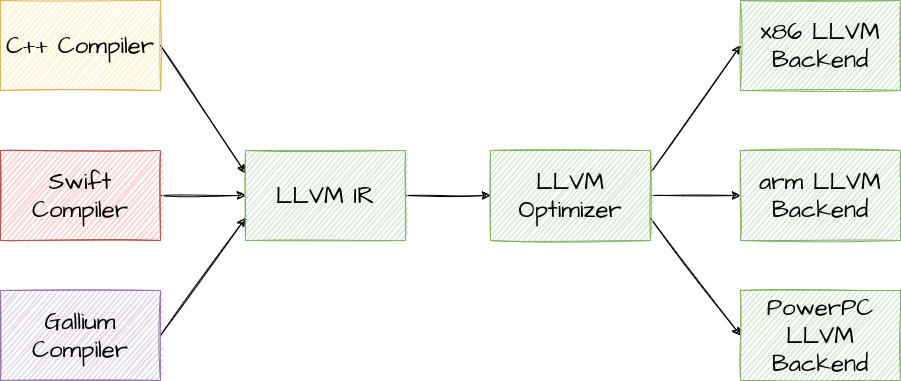

LLVM (no, it doesn’t stand for anything) is the backbone of this entire compiler. It’s a framework for writing compilers that provides a unified code generation target for many compilers, that handles doing complex optimization and generating actual machine code for different CPU configurations.

Instead of directly generating machine instructions (those differ between CPU architectures, and sometimes between CPU models), a compiler using LLVM instead will generate “LLVM IR” (LLVM Intermediary Representation).

This IR is then fed through a huge number of LLVM optimization passes that are specifically designed to operate on and output LLVM IR, and at the end you end up with LLVM IR that’s actually a relatively efficient way of representing a computation.

You can then plug this LLVM IR into one of the LLVM code generators, and you can get native assembly or object code.

This drastically simplifies writing a compiler for the language designers, as they no longer need to reinvent the wheel for how to optimize programs and how to generate efficient code for a huge variety of CPUs, all with different performance characteristics and available features.

LLVM IR

LLVM IR is not quite assembly, but it’s around the same level of verbosity. The main difference is twofold:

- Unlike normal CPUs, LLVM has infinite “virtual” registers

- LLVM is statically typed

define i32 @square_and_divide_by_x_plus_three(i32 %x) {

entry:

%0 = mul i32 %x, %x ; multiply x by itself, bind result to `%0`

%1 = add i32 %x, 3 ; add 3 to x, bind result to `%1`

%2 = sdiv i32 %0, %1 ; divide `%0` by `%1`, bind result to `%2`

ret i32 %2 ; return the result of `sdiv i32 %0, %1`

}

Unlike normal imperative languages however, things like %name = something aren’t variable

declarations: you cannot modify %name once you’ve given it a value. This is because in LLVM,

%name is literally just an alias for the operation something.

This is a subtle distinction, but it means that you can’t just re-assign a value:

%tmp = add i32 1, 1 ; `%tmp` is the operation `1 + 1`

%tmp = sub i32 %tmp, 1 ; error: `%tmp` is already assigned to `add i32 1, 1`

While this property makes it more difficult to form LLVM IR from a source AST,

it also means some optimizations are trivial: if %thing is never used after it’s defined,

it is guaranteed that whatever it did was not relied on, and it can be removed entirely

from the program (excluding a few edge cases, but those are not “normal” cases).

This property of “everything can only be assigned once” is known as SSA form, you can read more about it on Wikipedia: Static Single Assignment Form.

For an in-depth explanation of how to use LLVM IR, I would recommend you watch this video as an introduction to the real semantics of LLVM. You will also need to get very used to Ctrl+F-ing on the LLVM LangRef page.

For a hands-on tutorial that actually uses LLVM IR, see the LLVM Kaleidoscope Tutorial. While it focuses on using a JIT, it also has a section on emitting object code, and when using LLVM for JIT compilers you’re still generating LLVM IR just like you would for a normal ahead-of-time compiler.

I highly recommend at least doing the Kaleidoscope tutorial, and preferably also watching the linked video. LLVM is complicated, the API documentation is mixed at best, and just trying to figure it out yourself is hard at the very beginning of the learning process. You won’t regret spending a few hours on those resources, I promise.

The rest of this document assumes you have a basic understanding of LLVM IR.

Memory & Mutability

If we can’t re-assign values, how do we represent something like the following?

mut x = 5

x = x + 6

Technically, there are two options:

-

Since LLVM is an SSA representation, you could model this using pure SSA with

phis and just figuring out where exactly in your codexstops meaning5and starts meaning5 + 6. You could write some extremely complicated algorithms to accomplish this when more complex semantics come into play, i.e.ifand references/pointers. -

You could use LLVM’s memory abstraction to model this almost exactly as it works at the language level, and rely on LLVM’s optimization passes to properly turn this into the pure SSA form.

The correct answer here is memory. LLVM knows how complicated and error-prone it is to form

the proper SSA form, and they don’t expect you to. Instead, they expect a compiler that generates

LLVM IR to just assume they have infinite stack space, and alloca/load/store everywhere.

This is even what Clang, the C++ compiler that the LLVM project created alongside LLVM itself does.

The following IR correctly models the code example above:

%x = alloca i32 ; allocate space for an i32 on the stack, give `%x` a pointer to the space

store i32 5, i32* %x ; store `5` to the storage pointed to by `%ptr`

%value = load i32, i32* %x ; load the value that's pointed to by `%ptr`, 5 right now

%newvalue = add i32 %value, 6 ; add 6 to that value

store i32 %newvalue, i32* %x ; store `%value + 6` to `%x`

Once you’ve modeled your semantics with LLVM’s memory abstraction, LLVM’s mem2reg optimization pass can be

used to remove this. mem2reg is one of the main passes and is included in every default set of optimizations

starting at -O1, and it is very good at its job. It contains all the complex lifetime tracing code and the

carefully-tuned algorithms that form proper SSA from your IR that uses memory, so you don’t have to.

Don’t worry about emitting proper SSA form where it isn’t fairly trivial to do so, it’s a waste of time.

IR Generation Tips

In general, the best approach for “how should I generate IR for this code” is “do what Clang does.” The reasoning for this is pretty simple: Clang is the main LLVM front-end, and optimizations are usually focused on Clang first. Optimizations look for the patterns that Clang emits first, and sometimes other patterns afterwards. If you just emit something similar to what Clang does, you’ll usually have better luck.

Make a code sample in C or C++, plug it into Godbolt and give LLVM

the -emit-llvm and -O0 flags. Any other optimization level will show you the LLVM IR that Clang has

after it’s been sent through the LLVM optimization pipeline, and that IR is not what Clang actually generates.

If you want to see if Clang does anything different at different optimization levels without

LLVM’s optimizers being used, you can also add -Xclang -disable-llvm-passes to the compiler flags. This

will tell Clang to emit IR as-if it was going to be optimized, but it disables any of the LLVM optimizations

from actually being called.

Exceptions to the Rule

Clang likes to use explicit align arguments on every instruction, this is not really required. If you

don’t provide alignment arguments, LLVM will figure out the alignment based on the target triple and

data-layout specified in the module.

You probably don’t want to deal with that yourself, unless you’re handling different targets and their respective ABIs inside your code and not just handing the info to LLVM. See When to specify alignment

Note: If you don’t specify a target triple and a data layout for your module, LLVM’s default alignment will absolutely be wrong in some places, and will probably cause undefined behavior.

LLVM will also emit C/C++-specific pointer aliasing information (the !tbaa things), and debug

information (the !dbg things). Whether you want that or not is up to you, but it is certainly

not necessary.

Simplification

As a good rule of thumb, emit the most straightforward CFG-like IR you can. While sometimes

you can pretty easily figure out “yea, I could use a select here” for example, it’s probably

much simpler to remove the code that matches special cases where the more specialized instructions

would work as expected and just emit the branching code that you’d use otherwise.

Optimization passes work a lot on canonicalization, which in normal terms means “making all the possible ways of expressing this idea look the same” so it’s simpler for optimization passes to find the patterns in the IR that they are able to optimize.

As an example, consider the near infinite number of different ways to check that x != 5:

; v1

%0 = icmp eq i32 %x, 5 ; check if == 5

%1 = xor i1 %0, true ; invert the result

; v2

%0 = icmp ne i32 %x, 5 ; check if != 5

; v3

%0 = icmp slt %x, 5

%1 = icmp sgt %x, 5

%2 = or i1 %0, %1 ; check if x > 5 or x < 5

; v4

%0 = icmp eq i32 %x, 5 ; check if x == 5

%1 = sub i1 %0, 1 ; subtract 1, rely on wrapping to invert

; vN

; ...

Instead of checking every possible way of representing that, canonicalization passes work to make them all the same, and then optimization passes just look for the canonical version.

If you try to generate “simple” IR, you’re much more likely to end up with IR that can be properly canonicalized. This lines up with “do what Clang does”: Clang generates IR that works well with the canonicalization passes.

Optimizations

See this video by Chandler Carruth. Great introduction to gaining a mental model of the LLVM optimizer.

In general, if you don’t know what you want, just using the default O{0|1|2|3} pass pipeline

seems to work well enough. If you do know what you want, those are a good starting point

for adding additional passes.

Another good rule of thumb: if running the O3 pipeline a second time over your IR

improves the IR over just one O3 run, you probably need to look into changing your

pass ordering.

Performance Tips for Frontend Authors is also another good place to look if you’re having trouble.