Type Analysis: Analyzing and Understanding Programs

As was mentioned in the High Level Overview section, after we’ve successfully parsed a program, we need to analyze it. We need to ensure that the program actually makes sense in context.

Background: What Is a “Type”?

Before we can explain what type-based analysis is and how we do it, we need to establish what a type even is.

You’ve probably heard before that “computers only understand binary.” This is technically correct: the only thing your computer actually operates on is big sets of 1s and 0s. But, in reality, those sets of 1s and 0s can mean vastly different things depending on the meaning that our program assigns to them.

As an example, let’s consider the following 64 0s and 1s (a 0 or a 1 will be called a “bit” from now on):

0100101001101111011010000110111000100000010001000110111101100101

I’d wager that this looks pretty meaningless to you, and you’re completely right. There is no inherent meaning in these bits! There are quite literally trillions of valid ways we could interpret this data, depending on what type of data we pretend it contains.

If we treat it as containing a single integer, we would get exactly 5,363,620,503,418,597,221, or approximately 5.3 quintillion.

0100101001101111011010000110111000100000010001000110111101100101

^

5,363,620,503,418,597,221

We could also treat it as containing two integers, by making two 32 bit sections and treating each as individual integers. If we do that, we get 1,248,815,214 in the first 32 bits, and 541,355,877 in the second 32 bits.

01001010011011110110100001101110 00100000010001000110111101100101

^ ^

1,248,815,214 541,355,877

If we treat it as containing text, we could break it into 8 chunks of 8, and treat each chunk as a letter. When we do so, we get the text “John Doe”:

01001010 01101111 01101000 01101110 00100000 01000100 01101111 01100101

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

J O H N <space> D O E

No, I am not making this up. That is actually the exact bit pattern that contains “

John Doe” on your computer, at least in some programs. If you’re interested (and aren’t scared of extremely boring technical explanations), see UTF-8 on Wikipedia.

Point is, there are many different ways of interpreting these bits. The list above isn’t exhaustive of course: when you make up the rules, you can say that those bits mean literally anything you want! Now, consider that your computer could be operating on quite literally billions of these at a time, and that the example shown is only 64 of them. It’s just not reasonable for a human programmer to “just remember” what everything is!

And that is where types come in. Types give us a way to categorize these bits, and say that “this section of bits represent text,” or “this section of bits represents a 3D coordinate” or “these bits represent a fraction” or “these bits represent a single musical note.”

When we pair types with a programming language, they give us a way to automate all of this bit-hackery. Instead of thinking about programs as “these bits contain <something>”, we can think of it as “we have a value of <some type> that contains <some value>.” Better yet, we can teach the computer how to understand these types, and let the computer do some of the work for us.

Type Checking

Now that we’ve established what a type is, how do we actually integrate this into a language?

Recall back to the last section, where we discussed an “AST.” We’ll be using a very similar style of AST for this article,

with one slight modification: we will have values that model text, they will be represented as a value "With something inside quotes, like this".

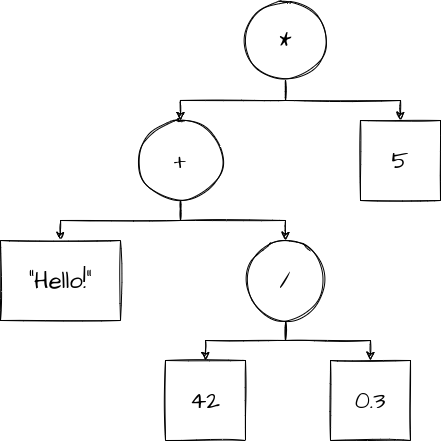

Consider the following AST that models ("Hello!" + (42 / 0.3)) * 5:

Let’s pretend for a moment that we just created this AST from parsing some imaginary language, and we aren’t sure if it makes sense. In order to check if it does, we need to perform type checking it.

Note: For the sake of correct terminology, I will be calling the circles/squares/rectangles of the AST a “node”.

In type-checking, we are trying to verify that a program makes sense. In order to actually do this, we need to start trying to figure out what each node of the AST is, what its type is, and whether that makes sense in context.

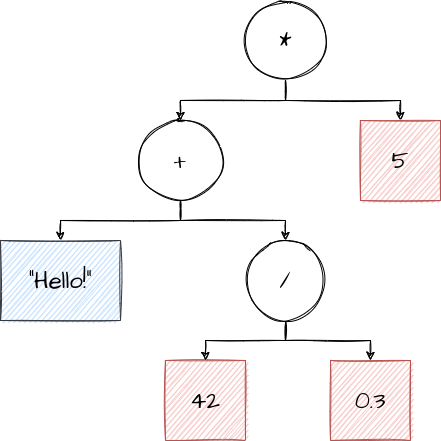

Let’s color code it. Nodes that are white are nodes that we haven’t verified yet, nodes that are blue are text, and nodes that are red are numbers.

An Invalid Program

As a first step, let’s deal with all of the simple nodes and figure out what those are first. We can just look at 5,

42 and 0.3 and tell that they are numbers, so we mark them as such. We can also look at "Hello!" and see that it is

quite obviously not a number, so we mark it as text.

Now, we need to look at the more complicated nodes *, + and /. For each of these, both of the nodes

that are being operated on have to be numbers. After all, you can’t multiply 5 by Muffin, can you?

For /, we know this is fine. Both 42 and 0.3 are numbers, so 42 / 0.3 makes sense. We can mark it as

being a number, because 42 / 0.3 is equivalent to a number.

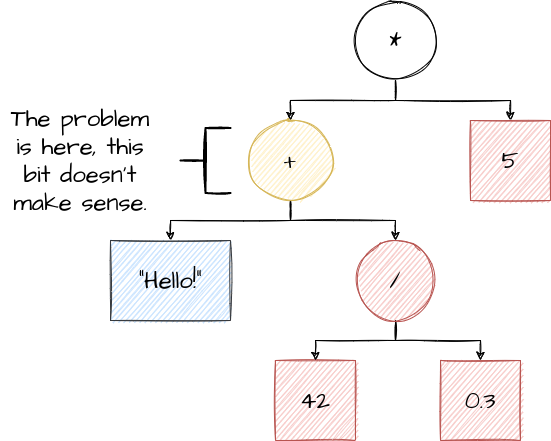

For + however, we have a problem! While the / node is (equivalent to) a number, "Hello!" isn’t! It doesn’t

make sense to add "Hello!" to a number. We’ve discovered a place in this program where our expectations were wrong,

so we know that this program is invalid. It has failed type checking.

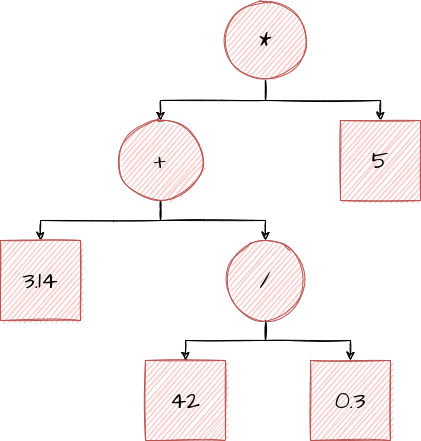

A Valid Program

Let’s say we switch out that "Hello!" node for something that

actually can be a number, like 3.14. What would happen in that case?

Well, we’d be able to verify +. After all, the result of 42 / 0.3 is a number, and so is 3.14. Since addition results in a number, we mark that node as well.

We can then do the same for *: the result of + is a number, and so is 5. We can mark the * as a number, since it also results in a number.

This time, we didn’t find anything weird! It successfully passed type checking without anything weird being found, so we know that the program makes sense. We can say that it is valid.

Conclusion

Type-checking is an extremely important part of the compiler. Later parts of the compiler use the AST extensively, and more importantly, they rely on the assumption that the AST is completely correct.

Type-checking both helps the programmer (as a failed type check can tell the programmer “Oh crap, I made a mistake”), and it helps the compiler.