High Level Overview of a Compiler’s Job

In the previous article, we explored the fundamental problem of programming computers: the computers don’t understand the humans, and vice-versa.

We also explored the idea of a compiler vs. an interpreter, for the most part these articles will focus on compilers exclusively from now on.

While interpreters are definitely interesting and a challenge on their own, compilers are much easier to reason about at a high level (meaning they’re much easier to write about).

Overall Job

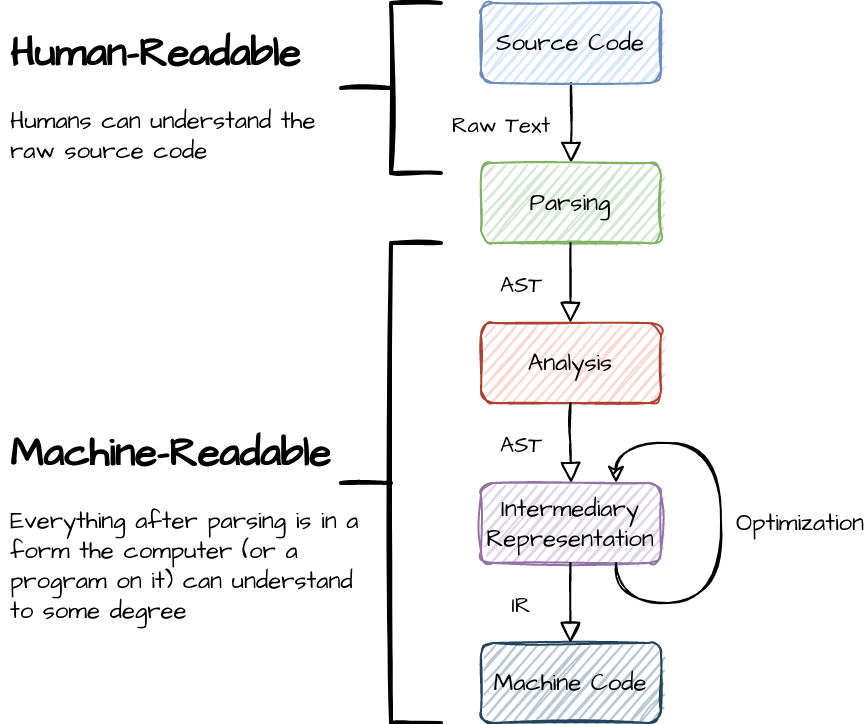

If you recall, the basic goal of a compiler is to translate what a human can understand to something that a computer can understand. At its core a compiler is simply trying to make sense of text, and it has many different “representations” that it uses to do so.

Just like we have different ways of representing human ideas (words, math notation, images, etc.), the compiler has different ways of representing ideas that help it to better do its job.

Note that any acronyms used will be explained below.

Each phase transforms and manipulates the representation of the previous, moving it’s internal representation of the program the human wrote closer and closer to machine code.

Phases

Articles going into much more depth on each of these will be published later, these are a very general overview of each phase and what they do.

Source Code

As mentioned in the previous article, source code is quite literally text in a .txt file, just with a different file name.

In order for a compiler to understand that code however, it must follow some sort of defined grammatical and semantic rules that the compiler is able to understand.

Think of it like English, where “walked home Joe” is nonsensical while “Joe walked home” is valid and understandable.

Parsing

“Parsing” is effectively computer jargon for “reading and making sense of text,” in this case the computer is reading in the source code that a human wrote, and trying to figure out what the source code means. Once it figures that out, it turns it into a representation that the compiler can then begin to actually understand and manipulate.

Think of this like breaking down an English sentence into subject(s), verbs operating on those subjects, and other parts of a sentence, and figuring out what each part refers to/means.

This representation is typically called an “AST.” This is actually an abbreviation for “abstract syntax tree,” but you don’t need to remember what it stands for right now. What an “AST” actually is will be explained in a later article, for now you can just think of it as “a representation of the program that the computer can reason about.”

Analysis

This step varies wildly depending on the programming language / compiler, but in general this amounts to “making sure the code makes sense.”

A decent analogy would be understanding English, many sentences are grammatically correct but nonsensical (“Colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” for example). The analysis step filters out those “correct” but nonsensical programs.

The AST is looked over, and each small part is checked for correctness and that each part “makes sense” both by itself and in the context of the rest of the AST.

Intermediary Representation (IR)

IR acts as an “intermediary” step in translating between machine code and the AST.

Machine code is obscenely pedantic and low-level, and the AST is meant to be extremely abstract and high-level. Translating between these two is possible but difficult; thus, in order to simplify the translation, the IR tries to be somewhere in the middle: more detailed than the AST, but not quite to the same extent as machine code.

The AST can then be translated into the IR in a (more) straightforward way, and then the IR can be translated to machine code in a (more) straightforward way.

Optimization

IRs also make it easy for compilers to do automated optimization, enabling a “smart” compiler to rewrite parts of a program in order to make them faster for the computer to actually execute.

These tricks can be math trickery, reducing/removing unnecessary work, or much more complex and wider-reaching optimizations that I can’t explain in a single sentence (or even a few paragraphs, for that matter).

Note: Nearly all modern research into compilers is going into optimization, because for the most part the other parts of compilers are “solved problems” and thus do not warrant as much effort for research.

Optimization is by far the most complex part of any compiler, and due to that it will not be covered very deeply in these articles. Some of the more trivial/easily-understandable optimizations may be explored, but most of them are simply too complex for me to explain effectively and succinctly.

Machine Code

Finally, this step is the result of the compiler: a program the computer understands.

The IR is fully translated into machine code, and then that machine code is put into a file (usually an .exe) that a user can then execute.